All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Validation Study of Malay (Bahasa Melayu) Version of the Dialectical Behavior Therapy- Ways of Coping Checklist (DBT-WCCL) and its Psychometric Properties

Abstract

Introduction

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy-Ways of Coping Checklist (DBT-WCCL) is widely used to assess coping strategies after a DBT intervention. This study aimed to validate the Malay adaptation of the DBT-WCCL and assess its psychometric properties.

Methods

A total of 300 bilingual university students participated in the validation process. The DBT-WCCL was translated into Malay using standardized translation and back-translation procedures with expert reviews. Both the English and Malay versions were administered alongside the Mindfulness Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS) for correlation analysis.

Results

The Malay version DBT-WCCL demonstrated reliability comparable to the original version across three subscales, with most items achieving Cronbach's α >0.80. Confirmatory factor analysis showed strong factor loadings (>0.3) and good model fit indices (CFI and TLI > 0.90; RMSEA and SRMR < 0.08).

Discussion

The discussion highlights that the Malay version of the DBT-WCCL demonstrates generally strong reliability and validity, particularly for the Blaming Others subscale, though certain items showed weak psychometric performance due to possible cultural mismatches.

Conclusion

The Malay version of the DBT-WCCL demonstrated preliminary evidence reliability and validity. However, cultural limitations suggest that a locally adapted version may enhance its future use in Malaysian clinical and research settings.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Dialectical Behavior Therapy

Linehan founded Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) as an approach to help individuals deal with self-harming and suicidal behaviors within the framework of cognitive behavioral therapy [1]. DBT, classified as third-wave psychotherapy, has been adapted from cognitive behavioral therapy to incorporate mindfulness and acceptance-based techniques [2, 3]. The core principles of DBT are derived from dialectical philosophy, biosocial theory, and behavioral theories, such as classical and operant conditioning [4]. The comprehensive delivery of DBT includes four components: individual therapy, group skills training, telephone coaching, and therapist consultation groups [2, 3]. The main goal of DBT is to help individuals replace ineffective behaviors with more adaptive ones, enabling them to address challenges, reach their goals, and lead a fulfilling life [3, 5, 6]. The skills taught encompass awareness, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, and emotion regulation, with an additional skill called middle path explicitly designed for adolescent patients [3, 7-9].

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is widely recognized as an evidence-based intervention effective in treating individuals with emotional dysregulation, identity disturbances, and impulsive or self-harming behaviors—symptoms often associated with borderline personality disorder (BPD) [3, 5, 10, 11]. Beyond BPD, DBT has been successfully applied to other psychiatric conditions, including substance use disorders, PTSD, mood and anxiety disorders, and eating disorders [12-15]. Central to DBT’s therapeutic process is the measurement and reinforcement of coping behaviors, for which tools such as the Ways of Coping Checklist (WCCL) and its DBT-specific version (DBT-WCCL) have been instrumental.

1.2. Development of DBT- WCCL

In response to the growing emphasis on culturally sensitive assessment tools, Neacsiu et al. [16] introduced the Dialectical Behavior Therapy Ways of Coping Checklist (DBT-WCCL) as a specialized tool to measure the utilization of DBT skills.

The DBT-WCCL is used to assess clients’ use of DBT-specific coping skills, as well as dysfunctional coping patterns, throughout therapy. It serves primarily as an outcome measure to evaluate the effectiveness of DBT interventions by tracking skill acquisition and reductions in maladaptive coping. Additionally, clinicians may use it as a measurement tool to identify areas where DBT use is lacking or dysfunctional coping remains prominent to make amends in the therapy approach. Its dual capacity as a progress-monitoring and outcome-assessing instrument makes it valuable for both clinical practice and research purposes.

Derived from the Revised Ways of Coping Checklist (RWCCL) [17, 18], the DBT-WCCL underwent rigorous validation procedures, including factor analysis, to establish its robust psychometric properties. The instrument was meticulously designed to capture two distinct subscales: the DBT Skills Subscale (DSS) and the Dysfunctional Coping Subscale (DCS), demonstrating high levels of reliability and validity. The scale exhibited promising psychometric characteristics, with principal component analysis serving as an initial tool for exploring item structure. Its overall validity was established through multiple forms of evidence, including internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity assessments such as confirmatory factor analysis and correlations with related constructs. Moreover, the DSS component of the DBT-WCCL effectively distinguished patients who underwent skills training over a 4-month treatment period from those who did not, underscoring its usefulness in evaluating the acquisition and application of DBT skills. The strong psychometric properties and discriminative capacity of the DBT-WCCL suggest its potential as a valuable instrument for assessing the use of DBT skills in therapy, providing researchers and practitioners with a comprehensive tool for monitoring and evaluating treatment progress in individuals undergoing DBT interventions [16, 19].

This study aimed to validate the Malay adaptation of the DBT-WCCL and assess its psychometric properties. The cultural adaptation of psychological assessment instruments holds significant importance in ensuring the precision and reliability of measurements, particularly when working with diverse populations [20]. While translation ensures linguistic accuracy, cultural adaptation ensures that psychological constructs are interpreted meaningfully within the local context. In cross-cultural psychology, constructs such as coping can be deeply influenced by religious beliefs, collectivist norms, and context-specific idioms of distress. Thus, adaptation processes must consider both language equivalence and cultural nuance [21]. The aim of this study was to strike that balance by incorporating expert reviews into the translation process, ensuring the final instrument not only reflects the original theoretical constructs but also resonates with local lived experiences.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

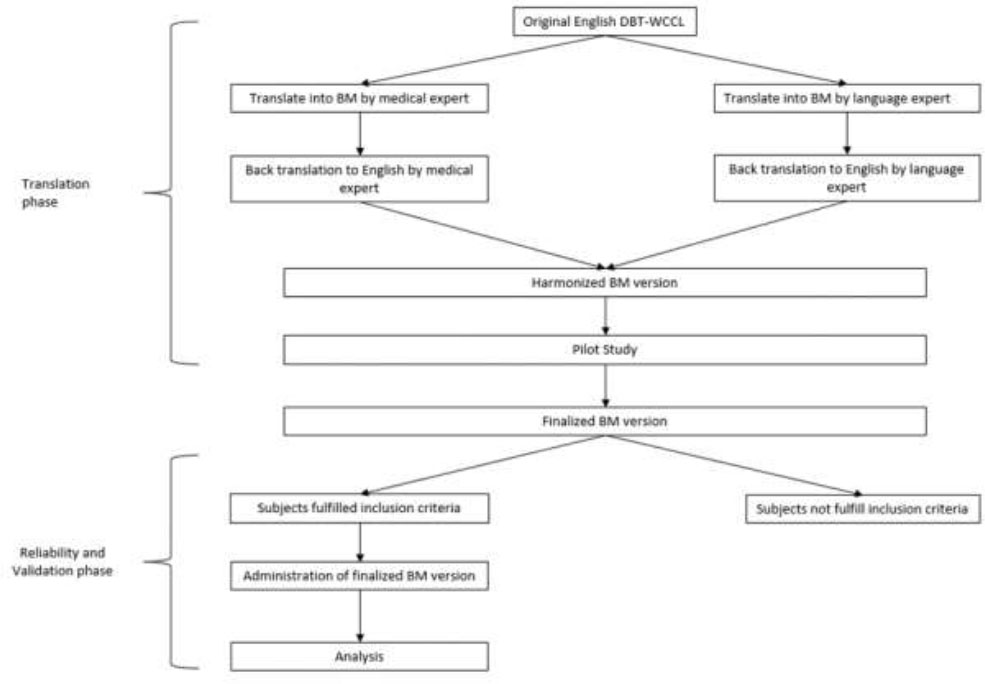

This study involves translation, cultural adaptation, and validation of the Dialectical Behaviour Therapy Ways of Coping Checklist (DBT-WCCL) for use in a Malay-speaking population in Malaysia. This study employed internationally recognized procedures for cross-cultural adaptation, followed by a series of psychometric analyses to examine the reliability and construct validity of the translated scale. The study procedures are outlined in the flowchart (Fig. 1).

2.1. Translation Process

The researchers contacted the original author and obtained permission to use the DBT-WCCL, confirming that it is free to use as it is in the public domain. Two DBT experts reviewed the original English version. Their opinions and suggestions were compiled, and amendments were made without significantly altering the original items. These revised English items were then used as the source text for forward translation into Bahasa Melayu. While this was done to aid understanding, we acknowledge that modifying the original English items prior to translation deviates from standard translation protocol and may affect the equivalence of the adapted version. The scale was then forward-translated into Bahasa Malaysia by two independent bilingual translators fluent in both languages. Both translators had expert-

Translation and validation flowchart.

ise in mental health terminologies and experience in translating psychological measures. The two translations were compared, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion to create a reconciled version that captured the intended meaning of the original items.

Backward translation of the reconciled version was conducted by another two bilingual translators who were blind to the original English version to ensure the accuracy and cultural relevance of the translation. The final Bahasa Malaysia version of the DBT-WCCL was reviewed by a panel of experts in both languages, including psychologists, linguists, and cultural experts, for content and linguistic equivalence. The panel reviewed each item for semantic and conceptual equivalence while also evaluating whether culturally specific coping expressions common in the Malay-speaking community were represented or missing. This review ensured that the translated items were clear, culturally appropriate, and conceptually equivalent to the original items. This process was integral to mitigating the risk of cultural bias and omission of contextually relevant coping mechanisms.

2.2. Pilot Study and Field Testing Process

A pilot study involving 30 bilingual university students was conducted to assess the face validity and item clarity of the translated DBT-WCCL. Participants provided feedback on item comprehension and cultural relevance. Their input informed minor linguistic adjustments to improve readability in Malay. These participants were not included in the final validation sample, and their data were used solely for refinement prior to large-scale field testing.

Field testing was conducted in a cross-sectional quantitative survey design. The convenience sampling method was used to recruit 300 university students in Malaysia who were literate in both Malay and English between 1st March 2024 to 31st April 2024. Information about the study was provided along with an informed consent form. Subjects who agreed to the study by signing an informed consent form were given the questionnaires. No identifiable personal information was collected. Submitted responses were not changeable by the participants post-submission and could not be repeated.

Subjects will answer a Malay-translated DBT-WCCL first, then The Malay Mindfulness Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS), followed by the original English DBT-WCCL. The sample was chosen from bilingual university students to ensure linguistic fluency and familiarity with self-report questionnaires, facilitating reliable comparison between English and Malay versions. This approach aligns with standard practice in initial validation studies aimed at establishing psychometric properties.

Inclusion criteria for participation were as follows: (i) aged 18 years and above, (ii) literate in both Malay and English, (iii) currently enrolled as a university student, (iv) no reported history of major psychiatric or neurological disorders (self-declared), (v) provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Participants were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (i) inability to comprehend both Malay and English languages, (ii) current or past diagnosis of major psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) or neurological conditions (e.g., epilepsy, traumatic brain injury), as self-reported, (iii) refusal or inability to provide informed consent.

All participants were non-clinical volunteers, and no individuals were pre-screened or recruited based on clinical psychological diagnoses such as borderline personality disorder (BPD).

2.3. Sample Size

The sample size was determined based on the proposed internal consistency of Cronbach’s α 0.5 and the desired effect size of 0.7 of a 59-item questionnaire, in accordance with widely accepted psychometric guidelines recommending a minimum subject-to-item ratio of 5:1, with a preferred ratio of 10:1 for robust factor analysis [5, 24]. Considering that the DBT-WCCL comprises 59 items, the ideal sample size was calculated to be 590 participants. However, due to practical limitations, a sample size of 300 was targeted, which meets the minimum acceptable threshold.

Required minimum sample size = Number of items × Minimum ratio (5:1) = 59 × 5 = 295 participants

The obtained sample of 300 participants thus satisfies the minimum requirement for factor analysis and internal consistency estimation in validation studies.

2.4. Malay Mindfulness, Attention, and Awareness Scale (MAAS)

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) was developed to evaluate attention and awareness in daily life. It is commonly utilized as a mindfulness assessment tool for the general population. Initially created by Brown and Ryan to use with adults in normative clinical settings, this 15-item self-reported scale focuses on the attention awareness aspect of mindfulness [25, 26]. The scale measures the frequency of mindful state experienced by individuals in everyday life through general and situation-specific statements. Scoring involved calculating the average performance across all 15 items, with scores ranging from 1 to 6 for each item. The total MAAS scores ranged from 15 to 90, with higher scores indicating a higher level of mindfulness.

The Malay Mindfulness Attention and Awareness Scale is a 15-item scale measuring the mindfulness level (MAAS) developed by Zainal et al., 2015 exhibiting strong internal consistency reliability, boasting a Cronbach's α value of 0.851, and demonstrated consistent results over 3 weeks. Through an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), the scale revealed three distinct factors: “Attention related to the general domain,” “Attention related to the physical domain,” and “Attention related to the psychological domain,” collectively explaining 52.09% of the total variance [26]. Notably, a significant correlation (r=0.82, p<0.01) was found between the Malay version of the MAAS and its English counterpart. Importantly, individuals with higher mindfulness scores showed a clear association with lower levels of mental disorders [27, 28].

2.5. DBT-WCCL English Version

The Dialectical Behavior Therapy Ways of Coping Checklist (DBT-WCCL) developed by Neacsiu et al. [16] is a comprehensive self-assessment tool comprising 59 items that evaluate the strategies employed in facing challenging situations within the last month. It is structured into two distinct subscales: one focusing on the DBT Skills Used and the other on dysfunctional coping skills, which can be further divided into “General Dysfunctional Coping” and “Blaming Others.” The internal reliability coefficient for the DBT Skills Use and dysfunctional coping subscale was determined to be 0.92 and 0.87, respectively [16].

The DBT-WCCL is widely used as both an outcome and process measure in Dialectical Behavior Therapy. It evaluates clients’ engagement with adaptive DBT skills and the presence of maladaptive coping strategies. The scale consists of three subscales: (1) Skills Use, (2) General Dysfunctional Coping, and (3) Blaming Others. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale (0 = Never used, 3 = Regularly used). The subscale scores are computed as the average of the responses across relevant items. A higher score on the Skills Use scale reflects greater application of DBT-based coping strategies, while higher scores on the dysfunctional subscales indicate reliance on maladaptive strategies [16].

The Skills Use subscale includes items such as “Talked to someone about how I’ve been feeling” and “Focused on the good things in my life.” The dysfunctional subscales assess tendencies like avoidance, denial, and externalizing blame. This scoring system allows practitioners and researchers to track progress, tailor interventions, and evaluate the efficacy of DBT over time.

2.6. Data Analysis Methods

The data analysis for validating the Malay version of the DBT-WCCL involved several steps to ensure the scale's reliability and validity [29]. Firstly, internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach's alpha to determine the reliability of the translated scale. Cronbach's alpha assesses how closely related a set of items are as a group, with higher values indicating greater internal consistency [30]. Each subscale, such as the Skills Use scale, general Dysfunctional Coping factor, and Blaming Others factor, was analyzed separately to ensure that the translated items reliably measured the intended constructs.

Item reliability was assessed using corrected item-total correlations, also referred to as item-rest correlations. This metric represents the correlation between an individual item and the sum of the remaining items within the same subscale, excluding the item itself. It provides insight into how well each item aligns with the overall construct measured by the subscale.

In addition to Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega, the Greatest Lower Bound (GLB) reliability coefficient was calculated for each subscale. GLB provides a lower-bound estimate of the scale’s true reliability and is often considered more precise when scale items differ in their true-score variances. It is particularly useful in psychometric evaluations where the assumptions of alpha (e.g., tau-equivalence) may not be fully met. A higher GLB value, typically above 0.80, indicates strong internal consistency and supports the robustness of the scale’s reliability [30].

To assess construct validity, both convergent and discriminant validity were examined. Convergent validity was evaluated by comparing the correlations between the translated scale and other measures of similar constructs, such as the MAAS. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the correlations between the translated scale and measures of dissimilar constructs. Theoretical expectations guided the evaluation, ensuring that items intended to measure similar constructs had higher correlations compared to items measuring different constructs. This process involved computing Pearson’s correlation coefficients to establish the degree of relatedness between the constructs, confirming that the translated scale appropriately captured the theoretical framework of the original DBT-WCCL [31]. To evaluate cross-language construct equivalence, Pearson correlation analyses were conducted between the subscale scores of the English and Malay versions of the DBT-WCCL. Each bilingual participant completed both versions of the scale, and subscale-level correlation coefficients were computed to determine the degree of concordance between the two language formats.

Factor structure analysis was conducted using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to validate the underlying factor structure of the translated DBT-WCCL. Each of the three subscales—Skills Use, General Dysfunctional Coping, and Blaming Others—was tested separately based on the original theoretical model by Neacsiu et al. [16], with one latent factor specified per subscale. The CFA was conducted using IBM SPSS AMOS (version 29), employing maximum likelihood estimation. As the underlying constructs were theoretically expected to be correlated, an oblique rotation method (e.g., Promax) was used to allow factor correlations.

Factor loadings, which indicate the strength and direction of the relationship between observed variables and latent constructs, were calculated for each item within the subscales. High factor loadings (generally above 0.3 or 0.4) indicated strong relationships and confirmed that the items were good indicators of the underlying constructs [32]. Model fit was assessed using multiple fit indices, including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Acceptable model fit was defined as CFI and TLI values above 0.90, RMSEA below 0.08, and SRMR below 0.08. These indices helped determine whether the proposed factor model adequately represented the data [33, 34].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Reliability Analysis

To assess the internal consistency of the Malay version of the Dialectical Behavior Therapy Ways of Coping Checklist (DBT-WCCL), several reliability analyses were conducted. Both item-level and scale-level reliability indicators were evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, McDonald’s omega, and the Greatest Lower Bound (GLB) [35].

3.2. Item Reliability of the Malay Version of DBT-WCCL

Item-level reliability for the Skills Use scale was examined using item-rest correlations and Cronbach’s alpha values if each item was deleted. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.905 to 0.913, indicating excellent internal consistency. As shown in Table 1, item-rest correlations varied substantially across items, with most values exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.30. Items such as Item 19 (“Focused on the good things in my life. [English version]”) and Item 23 (“Focused on the good aspects of my life… [English version]”) showed high item-rest correlations of 0.626 and 0.590, respectively. Conversely, some items such as Item 34 (“Told myself things could be worse. [English version]”) and Item 42 (“Thought how much better off I was than others. [English version]”) displayed notably lower correlations (0.072 and 0.182), suggesting a limited contribution to the overall construct.

Cronbach’s alpha values of the General Dysfunctional Coping factor, when each item was removed, ranged between 0.814 and 0.844. Item-rest correlations generally demonstrated adequate reliability, with several items showing

| - | Overall Cronbach’s α | 95% CI (Lower -Upper) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skills Use Scale | 0.910 | (0.895 - 0.923) | |

| Item | Item-rest Correlation | Mean | SD |

| 34. Told myself things could be worse. | 0.072* | 1.797 | 0.991 |

| 35. Occupied my mind with something else. | 0.288 | 2.072 | 0.899 |

| 42. Thought how much better off I was than others. | 0.182* | 0.928 | 0.858 |

| 43. Just took things one step at a time. | 0.183* | 1.693 | 0.907 |

| 57. Compared myself to others who are less fortunate. | 0.242 | 1.510 | 1.053 |

strong correlations (e.g., Item 25: 0.598; Item 45: 0.646). A few items (e.g., Item 17: 0.223 and Item 37: 0.208) exhibited weaker correlations, which may warrant further investigation or revision (Table 2).

| - | Overall Cronbach’s α | 95% CI(Lower -Upper) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skills Use Scale | 0.836 | (0.808 - 0.861) | |

| Item | Item-rest correlation | Mean | SD |

| 17. Wished I were a stronger person — more optimistic and forceful. | 0.223* | 2.507 | 0.674 |

| 37. Tried to make myself feel better by eating, drinking, smoking, taking medication, etc. | 0.208* | 0.950 | 1.059 |

The Blaming Others factor demonstrated lower overall item reliability compared to the other subscales. Cronbach’s alpha values if items were removed ranged from 0.624 to 0.795. Item-rest correlations were satisfactory for most items (e.g., Item 30: 0.685), though Item 48 (“Found out what the other person was responsible. [English version]”) had a notably low correlation of 0.060, suggesting that this item may not be well-aligned with the underlying factor (Table 3).

| - | Overall Cronbach’s α | 95% CI (Lower -Upper) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skills Use Scale | 0.723 | (0.673 - 0.768) | |

| Item | Item-rest correlation | Mean | SD |

| 48. Found out what the other person was responsible for. | 0.060* | 1.931 | 0.894 |

3.3. Scale/ Unidimensional Reliability of the Malay Version of DBT-WCCL

Scale-level internal consistency was also assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, McDonald’s omega (ω), and the Greatest Lower Bound (GLB) estimates. The Skills Use scale demonstrated excellent reliability in both the Malay and English versions. Specifically, the Malay version achieved α = 0.910, ω = 0.907, and GLB = 0.966. The English version reported even higher values (α = 0.938, ω = 0.937, GLB = 0.976) (Table 4).

For the General Dysfunctional Coping factor, internal consistency was also acceptable, with the Malay version producing α = 0.836, ω = 0.841, and GLB = 0.904. The English version demonstrated slightly better consistency (α = 0.876, ω = 0.878, GLB = 0.926) (see Table 5).

The Blaming Others factor showed lower reliability overall. In the Malay version, α = 0.723, ω = 0.749, and GLB = 0.775, while the English version showed modest improvement (α = 0.808, ω = 0.816, GLB = 0.841) (see Table 6). These findings suggest that while the scale is consistent overall, some factors may benefit from item refinement, especially in the Malay adaptation.

3.4. Validity Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the construct validity of the translated scales by examining the factor loadings of individual items.

3.4.1. Skill Use Scale

Table 7 represents, most items on the Skills Use scale loaded significantly onto the intended factor, with factor loadings ranging from 0.193 to 0.583. However, while some lower loadings (e.g., below 0.30) reached statistical significance due to the sample size, their contribution to construct validity is limited and should be interpreted with caution.

High loadings were observed for items such as Item 50 (“Told myself how much I had already accomplished. [English version]”, loading = 0.583) and Item 23 (“Focused on the good aspects of my life… [English version]”, loading = 0.562), indicating strong relationships with the latent factor. However, several items had lower loadings, including Item 34 (–0.024), suggesting weak or inconsistent relationships with the Skills Use factor.

3.4.2. General Dysfunctional Coping Factor

Table 8 represents, items within the General Dysfunctional Coping factor displayed varying loadings, with some falling below acceptable thresholds. It demonstrated largely adequate factor loadings, ranging from 0.171 (Item 17) to 0.670 (Item 45). Items such as Item 25 (“Felt bad that… [English version]”) and Item 45 (“Wished the situation would go away… [English version]”) showed robust loadings (>0.63), indicating they are strong indicators of the underlying construct. Although all loadings were statistically significant, several items (e.g., Item 17: loading = 0.171; Item 37: loading = 0.223) demonstrated poor practical significance, suggesting weak alignment with the underlying factor and the need for further psychometric review.

3.4.3. Blaming Others Factor

The factor loadings for the Blaming Others subscale are listed in Table 9, where most items met acceptable loading criteria. The strongest loading was observed for Item 30 (“Blamed others. [English version]”, loading = 0.641). Item 48 again showed problematic loading (0.069, p > .05), suggesting a poor representation of the intended factor.

| - | McDonald's ω | Cronbach's α | Greatest Lower Bound | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skill Use | Estimate | 95% CI (Lower – Upper) |

Estimate | 95% CI (Lower – Upper) |

Estimate | 95% CI (Lower – Upper) |

| Malay Version | 0.907 | (0.892 - 0.922) | 0.910 | (0.895 - 0.923) | 0.966 | (0.967 - 0.978) |

| English Version | 0.937 | (0.927 – 0.947) | 0.895 | (0.927 – 0.947) | 0.976 | (0.977 – 0.986) |

| - | McDonald's ω | Cronbach's α | Greatest Lower Bound | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Dysfunctional Coping | Estimate | 95% CI (Lower – Upper) |

Estimate | 95% CI (Lower – Upper) |

Estimate | 95% CI (Lower – Upper) |

| Malay Version | 0.841 | (0.814 – 0.867) | 0.836 | (0.808 – 0.861) | 0.966 | (0.893 - 0.929) |

| English Version | 0.878 | (0.858 – 0.898) | 0.876 | (0.854 – 0.895) | 0.976 | (0.919 – 0.946) |

| - | McDonald's ω | Cronbach's α | Greatest Lower Bound | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blaming Others | Estimate | 95% CI (Lower – Upper) |

Estimate | 95% CI (Lower – Upper) |

Estimate | 95% CI (Lower – Upper) |

| Malay Version | 0.749 | (0.706 – 0.792) | 0.723 | (0.673 – 0.768) | 0.775 | (0.737 - 0.830) |

| English Version | 0.816 | (0.785 – 0.848) | 0.808 | (0.772 – 0.839) | 0.841 | (0.819 – 0.881) |

| - | - | - | - | - | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Indicator | Estimate | Std. Error | p | Lower | Upper |

| Skills use | 31. Listened to or played music that I found relaxing. | 0.252 | 0.048 | < .001 | 0.158 | 0.346 |

| 33. Accepted the next best thing to what I wanted. | 0.264 | 0.044 | < .001 | 0.177 | 0.351 | |

| 34. Told myself things could be worse. | -0.024* | 0.059 | 0.680 | -0.139 | 0.091 | |

| 35. Occupied my mind with something else. | 0.193 | 0.052 | < .001 | 0.090 | 0.295 | |

| 42. Thought how much better off I was than others. | 0.123 | 0.050 | 0.015 | 0.024 | 0.222 | |

| 43. Just took things one step at a time. | 0.109 | 0.053 | 0.041 | 0.004 | 0.213 | |

| 44. Did something to feel a totally different emotion (like going to a funny movie). | 0.239 | 0.054 | < .001 | 0.134 | 0.344 | |

| 56. Stepped back and tried to see things as they really are. | 0.280 | 0.049 | < .001 | 0.184 | 0.375 | |

| 57. Compared myself to others who are less fortunate. | 0.205 | 0.062 | < .001 | 0.084 | 0.326 | |

| - | 95% Confidence Interval | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Indicator | Estimate | Std. Error | p | Lower | Upper |

| General dysfunctional coping | 17. Wished I were a stronger person — more optimistic and forceful. | 0.171 | 0.041 | < .001 | 0.091 | 0.251 |

| 20. Wished that I could change the way that I felt. | 0.423 | 0.047 | < .001 | 0.331 | 0.515 | |

| 25. Felt bad that I couldn't avoid the problem. | 0.638 | 0.050 | < .001 | 0.540 | 0.735 | |

| 37. Tried to make myself feel better by eating, drinking, smoking, taking medication, etc. | 0.223 | 0.072 | 0.002 | 0.082 | 0.364 | |

| 45. Wished the situation would go away or somehow be finished. | 0.670 | 0.053 | < .001 | 0.567 | 0.773 | |

| - | 95% Confidence Interval | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Indicator | Estimate | Std. Error | p | Lower | Upper |

| Blaming others | 7. Figured out who to blame. | 0.623 | 0.051 | < .001 | 0.523 | 0.723 |

| 30. Blamed others. | 0.641 | 0.040 | < .001 | 0.562 | 0.721 | |

| 48. Found out what the other person was responsible for. | 0.069* | 0.056 | 0.215 | -0.040 | 0.179 | |

| 28. Thought that others were unfair to me. | 0.560 | 0.056 | < .001 | 0.451 | 0.669 | |

3.5. Model Fit Indices

The model fit for each factor structure was evaluated using multiple indices, including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR).

3.5.1. Skills Use Scale

The model fit indices indicated a suboptimal fit for the Skills Use scale. The CFI (0.728) and TLI (0.712) were below the acceptable threshold of 0.90, suggesting poor fit. However, RMSEA (0.070) and SRMR (0.069) were within acceptable ranges, indicating that the model fit the data moderately well (Table 10).

3.5.2. General Dysfunctional Coping Factor

The fit indices for the General dysfunctional coping factor were slightly improved, though still not ideal. CFI was 0.819, and TLI was 0.789, with RMSEA at 0.086 and SRMR at 0.062 (Table 11). The results suggest an adequate but not excellent fit of the model to the data.

3.5.3. Blaming Other Factors

The Blaming Others factor demonstrated an excellent model fit. Fit indices were all within or above the recommended thresholds: CFI = 0.989, TLI = 0.982, RMSEA = 0.042, and SRMR = 0.025 (Table 12). This supports the structural validity of this factor in the Malay version of the DBT-WCCL.

3.6. Cross-language Correlation Analysis

To assess the cross-language equivalence of the DBT-WCCL, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between the scores obtained from the English and Malay versions for each of the three subscales. These analyses were conducted among the same bilingual participants (n = 300) who completed both versions of the scale in a single session.

The results indicated strong and statistically significant correlations between the English and Malay versions across all subscales, supporting the convergent validity of the translated instrument (Table 13).

These findings suggest a high degree of construct equivalence between the original and translated versions of the DBT-WCCL, indicating that the Malay version reliably captures the same coping constructs assessed by the original English version.

| Chi-square Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Χ2 | df | p |

| Baseline model | 4380.737 | 703 | |

| Factor model | 1665.888 | 665 | < .001 |

| Fit Indices | |

|---|---|

| Index | Value |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.728 |

| Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.712 |

| Bentler-Bonett Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI) | 0.712 |

| Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.620 |

| Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI) | 0.586 |

| Bollen's Relative Fit Index (RFI) | 0.598 |

| Bollen's Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | 0.731 |

| Relative Noncentrality Index (RNI) | 0.728 |

| Other Fit Measures | |

|---|---|

| Metric | Value |

| Root Mean Square Error Of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.070 |

| RMSEA 90% CI lower bound | 0.066 |

| RMSEA 90% CI upper bound | 0.074 |

| RMSEA p-value | 0.000 |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.069 |

| Hoelter's critical N (α = .05) | 134.375 |

| Hoelter's critical N (α = .01) | 139.273 |

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.910 |

| McDonald’s Fit Index (MFI) | 0.195 |

| Expected Cross-Validation Index (ECVI) | 6.189 |

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Internal Consistency and Scale Reliability

The internal consistency values for the Malay version of the DBT-WCCL were generally strong and only modestly lower (by 0.02 to 0.08) than those of the original English version. These results suggest that the translated scale retains most of the reliability of the original, particularly for the Skills Use and General Dysfunctional Coping subscales. However, the slightly reduced reliability, especially in the Blaming Others subscale, may point to either linguistic limitations or cultural nuances affecting item interpretation.

| Chi-square Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Χ2 | df | p |

| Baseline model | 1220.676 | 105 | |

| Factor model | 292.251 | 90 | < .001 |

| Fit Indices | |

|---|---|

| Index | Value |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.819 |

| Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.789 |

| Bentler-Bonett Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI) | 0.789 |

| Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.761 |

| Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI) | 0.652 |

| Bollen's Relative Fit Index (RFI) | 0.721 |

| Bollen's Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | 0.821 |

| Relative Noncentrality Index (RNI) | 0.819 |

| Other Fit Measures | |

|---|---|

| Metric | Value |

| Root Mean Square Error Of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.086 |

| RMSEA 90% CI lower bound | 0.075 |

| RMSEA 90% CI upper bound | 0.097 |

| RMSEA p-value | 1.084×10-7 |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.062 |

| Hoelter's critical N (α = .05) | 119.468 |

| Hoelter's critical N (α = .01) | 130.955 |

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.970 |

| McDonald’s Fit Index (MFI) | 0.719 |

| Expected Cross-Validation Index (ECVI) | 1.249 |

Compared to the original study, which reported internal consistencies up to α = .96 for the DBT Skills Subscale (DSS) and α = .92 for the Dysfunctional Coping Subscale (DCS), the Malay version’s slightly lower coefficients still fall within acceptable psychometric standards. However, this subtle reduction in alpha values, particularly in the Blaming Others factor, may suggest that culturally mediated expressions of dysfunction differ in Malaysian populations and warrant further item-level examination [30, 32].

4.2. Item-Level and Structural Validity

statistical and practical significance is important to distinguish when interpreting factor loadings. Given the sample size, some items with low loadings (e.g., < 0.30) may have reached statistical significance, but their weak association with the latent factor questions their conceptual relevance.

Consistent with Neacsiu et al. [16], the present study found variability in item performance across subscales. Several items with low factor loadings (e.g., Item 34: “Told myself things could be worse”) may reflect constructs that are less salient or interpreted differently in Malay cultural contexts. In collectivist societies, coping strategies involving self-reassurance or downward comparison may be less commonly employed or may carry different connotations. This raises the question of whether such items should be retained. Based on our findings, we recommend that items with persistently low loadings and poor item-rest correlations be considered for either rewording to enhance cultural resonance or substitution with more culturally congruent equivalents. Future validation studies should include cognitive interviews and item-response analyses to determine whether low-loading items are conceptually unclear, culturally irrelevant, or merely underused in the target population.

| Chi-square Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Χ2 | df | p |

| Baseline model | 455.966 | 15 | |

| Factor model | 13.766 | 9 | 0.131 |

| Fit Indices | |

|---|---|

| Index | Value |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.989 |

| Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.982 |

| Bentler-Bonett Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI) | 0.982 |

| Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.970 |

| Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI) | 0.582 |

| Bollen's Relative Fit Index (RFI) | 0.950 |

| Bollen's Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | 0.989 |

| Relative Noncentrality Index (RNI) | 0.989 |

| Other Fit Measures | |

|---|---|

| Metric | Value |

| Root Mean Square Error Of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.042 |

| RMSEA 90% CI lower bound | 0.000 |

| RMSEA 90% CI upper bound | 0.083 |

| RMSEA p-value | 0.577 |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.025 |

| Hoelter's critical N (α = .05) | 377.098 |

| Hoelter's critical N (α = .01) | 482.621 |

| Goodness of fit index (GFI) | 0.996 |

| McDonald's Fit Index (MFI) | 0.992 |

| Expected Cross-Validation Index (ECVI) | 0.163 |

| Subscales (Malay vs. English Version) | Pearson's r | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Skill Use Scale | 0.810 | < .001 |

| General Dysfunctional Coping | 0.845 | < .001 |

| Blaming Others | 0.761 | < .001 |

Factor loadings for the Malay Skills Use scale ranged between 0.252 and 0.583 for most items, whereas the original version reported loadings as high as 0.79 for core skills-based items. Notably, several items in the translated version fell below the conventional loading threshold, including some mindfulness and comparison-based coping strategies. This suggests a potential conceptual or linguistic mismatch in the translation or cultural interpretation of these strategies. For instance, while the item “Told myself things could be worse” showed high factor alignment in the original version, the equivalent Malay item (Item 34) demonstrated negligible loading, possibly due to differences in how acceptance-based reappraisal is perceived cross-culturally [36].

Some items that exhibited low factor loadings (e.g., Item 34: “Told myself things could be worse”; Item 42: “Thought I was better than others”) may reflect themes that are culturally incongruent or less frequently endorsed in the Malaysian context. In collectivist cultures, such as Malaysia’s, individualistic self-elevating or self-comparison strategies may be perceived as socially undesirable or inconsistent with local norms of modesty and social harmony. Alternatively, these items may have simply been rarely chosen, which could explain their weak statistical association. While this study did not include a detailed item-level response distribution, data—such as the proportion of participants endorsing each item—would offer further insights into whether low-loading items are conceptually irrelevant or statistically underpowered due to low variance.

4.3. Model Fit and Factor Structure Comparison

Confirmatory factor analyses revealed substantial differences in model fit between the Malay and original versions. In Neacsiu et al. [16], exploratory principal components analysis yielded a clean three-factor structure explaining 41.1% of the variance, with excellent internal coherence and model parsimony. Conversely, in the Malay version, the Skills Use scale showed modest fit indices (CFI = 0.728; TLI = 0.712), suggesting a poorer fit of the hypothesized model to the observed data. While RMSEA (0.070) and SRMR (0.069) were within acceptable thresholds, the CFI and TLI values fall short of conventional cutoffs for acceptable model fit (≥ 0.90) [16].

In contrast, the Blaming Others subscale demonstrated excellent model fit (CFI = 0.989; RMSEA = 0.042), closely aligning with the original study’s findings that this factor is structurally robust and distinct. This may reflect the clear and behaviorally anchored nature of interpersonal blame, which tends to be less culturally variable and more easily captured across translations.

These discrepancies in model fit suggest that the Skills Use subscale, originally developed within a Western therapeutic framework, may not fully align with the culturally nuanced ways in which coping is conceptualized and enacted within Malaysia. While translation and back-translation procedures ensure semantic and linguistic fidelity, they may not fully address differences in cultural relevance or psychological interpretation. Malaysia is a multicultural society comprising diverse ethnic groups including Malay, Chinese, Indian, and Indigenous communities—each shaped by distinct cultural traditions, languages, and religious practices [13, 23]. As such, coping mechanisms may be influenced by cultural norms related to emotional expression, spirituality, family dynamics, and interpersonal behavior [17, 18].

These cultural distinctions highlight the need for a more localized or culturally adapted model of Skills Use that better reflects the Malaysian context. Future validation efforts should consider incorporating qualitative methods, such as cognitive interviews or focus groups, to explore culturally salient coping themes that the original DBT-WCCL may not capture. The development of culturally equivalent items or subscales—potentially through exploratory factor analysis of newly generated items—could enhance both the conceptual validity and clinical applicability of the instrument in Malaysia’s pluralistic society.

4.4. Cross-language Correlation

The strong and statistically significant correlations between the Malay and English versions of the DBT-WCCL subscales provide compelling evidence of cross-language construct validity. These results affirm that the translated Malay version preserves the conceptual integrity of the original instrument. The high correlation coefficients (ranging from 0.761 to 0.845) indicate that bilingual respondents interpreted and responded to the translated items in ways that were consistent with the English version. This finding reinforces the robustness of the translation and adaptation process and supports the scale’s applicability in bilingual and Malay-speaking clinical and research settings. Nonetheless, while the correlations support convergent validity, future studies should explore measurement invariance across languages to validate cross-cultural applicability further.

4.5. Implications for Cross-cultural Application of the DBT-WCCL

The comparison between the original and translated versions underscores the challenges of cross-cultural adaptation of psychological scales. While core components of DBT skills—such as emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness—appear psychometrically stable across languages, their cultural expression and the linguistic framing of individual items can significantly influence measurement validity. The poorer performance of certain acceptance and reappraisal items in the Malay sample suggests that these constructs may require more culturally tailored language or conceptual framing [21, 37].

Moreover, the original DBT-WCCL was validated in clinical samples predominantly comprising individuals diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) in Western contexts [20]. The present validation was conducted exclusively in a non-clinical university student population and did not include individuals with clinically diagnosed BPD or other psychiatric conditions. This may limit the generalizability of the findings, particularly regarding the instrument’s applicability in clinical settings where DBT is most commonly used [2, 3]. Given that DBT skills are used transdiagnostically, future studies should consider validating the Malay DBT-WCCL in clinical subgroups (e.g., individuals with emotional dysregulation, depression, or BPD) to better align with the population focus of the original study [20].

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

The validation of the Malay version of the DBT-WCCL demonstrates several strengths, including robust construct validity and generally high factor loadings, particularly for the Blaming Others factor. The convergent and discriminant validity analyses confirm that the translated scale aligns well with theoretical expectations, indicating that the scale measures the constructs effectively. Additionally, the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) for the Blaming Others factor showed excellent model fit indices, underscoring the precision with which it represents its underlying construct. This suggests that the translation process has retained the conceptual integrity of the original scale for this factor, making it a reliable tool for assessing coping mechanisms within this context.

However, there are notable limitations to this validation study. One of which is that some English items were slightly reworded before being translated, potentially introducing inconsistencies with the original DBT-WCCL. Future validation studies should avoid modifying the source instrument and should instead follow established cross-cultural adaptation guidelines, making content adjustments only after translation and expert cultural review.

The Skills Use and General Dysfunctional Coping factors showed less satisfactory model fit indices, indicating that these sections of the scale may require further refinement. Some items within these factors exhibited lower factor loadings, suggesting they may not be strong indicators of their respective constructs in the Malay context. This could be due to cultural differences in the expression and understanding of coping strategies, which were not fully captured during the translation process [21, 22]. The use of a homogeneous sample comprising bilingual university students may not represent the coping behaviors of older adults, individuals with lower education levels, or those from rural or lower-income communities. Further validation studies should include an analysis of response patterns (e.g., frequency of endorsement) and consider cognitive debriefing interviews to determine whether low-loading items are culturally inappropriate or underutilized.

Another limitation of this study is the absence of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to investigate whether an alternative factor structure might better represent the data within the Malaysian sample. While CFA was used to test the fit of the original theoretical model developed by Neacsiu et al. [16], the modest fit indices—particularly for the Skills Use and General Dysfunctional Coping subscales —suggest that the underlying factor structure may not fully align with coping constructs as experienced by Malaysian respondents. Future validation studies should incorporate EFA to explore the possibility of a culturally emergent structure, which could guide the refinement or development of localized subscales with improved construct validity.

Additionally, while the study provides initial evidence of validity, it would benefit from further validation with more diverse samples to ensure the scale's generalizability across different populations within the Malay-speaking community. Future research should also explore potential modifications to improve item clarity and relevance, thereby enhancing the overall reliability and validity of the scale.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the Malay version of the DBT-WCCL demon-strated satisfactory reliability and preliminary evidence of construct validity. When compared with the original English version developed by Neacsiu et al. [16], the translated scale retains core psychometric strengths, particularly in the Skills Use and Dysfunctional Coping subscales. However, differences in item performance and model fit suggest that additional cultural and linguistic calibration may enhance the measure’s effectiveness in Malaysian contexts. These findings reinforce the importance of culturally sensitive adaptation and validation processes when extending psy-chological instruments across linguistic boundaries.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the psychometric findings and the multicultural context of Malaysia, we recommend that future work prioritize the development of a culturally adapted version of the DBT-WCCL rather than relying solely on direct translation. Several items with weak psychometric performance —such as Item 34 (“Told myself things could be worse”), Item 42 (“Thought I was better than others”), Item 48 (“Recognized others’ responsibilities”), Item 17 (“Hoped to be a stronger, more optimistic and assertive person”), and Item 37 (“Tried to make myself feel better by eating, drinking, smoking, taking medication, etc.”)—should be carefully reviewed. These items may reflect coping concepts that are either culturally misaligned, socially discouraged, or infrequently used in the Malaysian context.

We propose that these items be either reworded to improve conceptual clarity and cultural resonance or replaced with newly developed items based on qualitative data from target populations. Cognitive interviews and focus groups involving individuals who are actively coping with emotional or situational distress (e.g., students under academic stress, individuals in treatment, or those from rural communities) may yield culturally salient coping strategies currently missing from the scale.

While we recommend retaining the original scoring structure for now to allow cross-cultural comparisons, any substantial revision to item content or factor structure should be followed by re-validation and potential re-evaluation of the scoring model (e.g., using item response theory or factor analytic specification).

Overall, we advocate for a shift from a Malaysian translation to a Malaysian adaptation of the DBT-WCCL, one that honors the pluralistic nature of the local culture while maintaining fidelity to the theoretical framework of Dialectical Behavior Therapy.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: V.C.T.: Study conception and design; A.K.: Data Analysis or Interpretation; N.M.N.H.: Methodology; H.B.L.: Visualization; N.T.P.P.: Writing the Paper; C.M.H.: Writing – reviewing and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| BPD | = Borderline Personality Disorder |

| CFA | = Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | = Comparative Fit Index |

| CI | = Confidence Interval |

| DBT | = Dialectical Behavior Therapy |

| DBT-WCCL | = Dialectical Behavior Therapy – Ways of Coping Checklist |

| DCS1 | = Dysfunctional Coping Subscale |

| DCS2 | = Blaming Others Subscale |

| DSS | = DBT Skills Subscale |

| EFA | = Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| GLB | = Greatest Lower Bound |

| MAAS | = Mindful Attention Awareness Scale |

| RMSEA | = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SD | = Standard Deviation |

| SRMR | = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| TLI | = Tucker–Lewis Index |

| α (alpha) | = Cronbach’s Alpha |

| ω (omega) | = McDonald’s Omega |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by The Research Ethics Committee of University Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia, approval code JKEtika 1/24(12).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study, with approval for scientific article publication.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article will be available from the corresponding author [A.K.] upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences of University Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia, for their support during the conduct of this study.

APPENDIX

| Item No. | Translated Malay Item | Original English Item |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Berunding atau berkompromi untuk mendapatkan sesuatu yang positif daripada situasi itu. | Bargained or compromised to get something positive from the situation. |

| 2 | Saya bersyukur atas nikmat yang diperolehi. | Counted my blessings. |

| 3 | Menyalahkan diri sendiri. | Blamed myself. |

| 4 | Tertumpu kepada perkara baik yang diperoleh daripada sesuatu. | Concentrated on something good that could come out of the whole thing. |

| 5 | Menyimpan perasaan sendiri. | Kept feelings to myself. |

| 6 | Memastikan saya membalas dengan cara yang tidak mengasingkan orang lain. | Made sure I'm responding in a way that doesn’t alienate others. |

| 7 | Memikirkan siapa yang harus dipersalahkan. | Figured out who to blame. |

| 8 | Berharap keajaiban akan berlaku. | Hoped a miracle would happen. |

| 9 | Cuba untuk fokus sebelum mengambil sebarang tindakan. | Tried to get centered before taking any action. |

| 10 | Bercakap dengan seseorang tentang perasaan saya. | Talked to someone about how I’ve been feeling. |

| 11 | Tetap dengan perjuangan saya dan berjuang untuk apa yang saya mahu. | Stood my ground and fought for what I wanted. |

| 12 | Tidak ingin mempercayai bahawa ia telah berlaku. | Refused to believe that it had happened. |

| 13 | Membelanjakan diri saya dengan sesuatu yang sangat lazat. | Treated myself to something really tasty. |

| 14 | Mengkritik atau membebel kepada diri sendiri. | Criticized or lectured myself. |

| 15 | Melepas geram dengan orang lain. | Took it out on others. |

| 16 | Memikirkan beberapa jalan penyelesaian yang berbeza untuk masalah saya. | Came up with a couple of different solutions to my problem. |

| 17 | Berharap semoga menjadi orang yang lebih tabah — lebih optimistik dan tegas. | Wished I were a stronger person — more optimistic and forceful. |

| 18 | Menerima perasaan saya yang kuat tentang sesuatu perkara, tetapi tidak membiarkan perasaan tersebut terlalu mengganggu perkara yang lain. | Accepted my strong feelings, but not let them interfere with other things too much. |

| 19 | Fokus kepada perkara yang baik dalam hidup saya. | Focused on the good things in my life. |

| 20 | Saya berharap saya boleh mengubah apa yang saya rasai. | Wished that I could change the way that I felt. |

| 21 | Menemui sesuatu yang indah dipandang agar membuatkan saya berasa lebih baik. | Found something beautiful to look at to make me feel better. |

| 22 | Mengubah sesuatu tentang diri saya supaya saya dapat menangani situasi dengan lebih baik. | Changed something about myself so that I could deal with the situation better. |

| 23 | Fokus kepada aspek baik dalam hidup saya dan kurang memberi perhatian kepada fikiran atau perasaan negatif. | Focused on the good aspects of my life and gave less attention to negative thoughts or feelings. |

| 24 | Marah kepada orang atau perkara yang menyebabkan berlakunya masalah. | Got mad at the people or things that caused the problem. |

| 25 | Saya rasa bersalah kerana saya tidak dapat mengelak daripada masalah itu. | Felt bad that I couldn't avoid the problem. |

| 26 | Cuba untuk mengalihkan perhatian diri sendiri dengan bergiat aktif. | Tried to distract myself by getting active. |

| 27 | Sedar tentang perkara yang perlu dilakukan, jadi saya telah menggandakan usaha saya dan berusaha lebih gigih untuk melaksanakan kerja itu. | Been aware of what has to be done, so I've been doubling my efforts and trying harder to make things work. |

| 28 | Memikirkan bahawa orang lain tidak adil terhadap saya. | Thought that others were unfair to me. |

| 29 | Menenangkan diri saya dengan menggunakan sejenis wangian yang harum di sekeliling. | Soothed myself by surrounding myself with a nice fragrance of some kind. |

| 30 | Menyalahkan orang lain. | Blamed others. |

| 31 | Mendengar atau memainkan muzik yang saya menenangkan diri saya. | Listened to or played music that I found relaxing. |

| 32 | Meneruskan sesuatu seolah-olah tiada apa yang berlaku. | Gone on as if nothing had happened. |

| 33 | Menerima perkara yang kedua terbaik untuk apa yang saya mahu. | Accepted the next best thing to what I wanted. |

| 34 | Memberitahu diri saya keadaan boleh menjadi lebih teruk. | Told myself things could be worse. |

| 35 | Menyibukkan fikiran saya dengan perkara lain. | Occupied my mind with something else. |

| 36 | Bercakap dengan seseorang yang boleh melakukan sesuatu perkara yang konkrit tentang masalah itu | Talked to someone who could do something concrete about the problem. |

| 37 | Cuba untuk membuat diri saya berasa lebih baik dengan makan, minum, merokok, mengambil ubat, dan lain-lain | Tried to make myself feel better by eating, drinking, smoking, taking medication, etc. |

| 38 | Cuba untuk tidak bertindak terlalu tergesa-gesa atau mengikut firasat saya sendiri. | Tried not to act too hastily or follow my own hunch. |

| 39 | Mengubah sesuatu supaya keadaan menjadi betul | Changed something so things would turn out right. |

| 40 | Memanjakan diri saya dengan sesuatu yang membawa sentuhan yang selesa (cth., mandi buih atau pelukan) | Pampered myself with something that felt good to the touch (e.g., a bubble bath or a hug). |

| 41 | Mengelak daripada berjumpa dengan orang. | Avoided people. |

| 42 | Terfikir bahawa saya lebih baik daripada orang lain. | Thought how much better off I was than others. |

| 43 | Hanya membuat sesuatu perkara dalam satu masa. | Just took things one step at a time. |

| 44 | Melakukan sesuatu perkara untuk merasakan emosi yang berbeza sama sekali (seperti menonton filem lucu). | Did something to feel a totally different emotion (like go to a funny movie). |

| 45 | Berharap agar keadaan tersebut akan hilang atau tiba-tiba tamat. | Wished the situation would go away or somehow be finished. |

| 46 | Mengelakkan orang lain daripada mengetahui betapa buruknya perkara tersebut. | Kept others from knowing how bad things were. |

| 47 | Memfokuskan tenaga saya untuk membantu orang lain. | Focused my energy on helping others. |

| 48 | Mengetahui apa tanggungjawab individu lain. | Found out what the other person was responsible. |

| 49 | Memastikan saya menjaga badan saya dan kekal sihat supaya saya kurang sensitif dari segi emosi. | Made sure to take care of my body and stay healthy so that I was less emotionally sensitive. |

| 50 | Memperingatkan diri saya bahawa banyak yang telah saya capai. | Told myself how much I had already accomplished. |

| 51 | Memastikan saya membalas dengan cara yang betul supaya saya masih boleh menghormati diri saya selepas itu. | Made sure I respond in a way so that I could still respect myself afterwards. |

| 52 | Saya berharap saya boleh mengubah apa yang telah berlaku. | Wished that I could change what had happened. |

| 53 | Membuat rancangan untuk bertindak dan mengikuti rancangan tersebut. | Made a plan of action and followed it. |

| 54 | Bercakap dengan seseorang untuk mengetahui apa yang berlaku dalam situasi itu. | Talked to someone to find out about the situation. |

| 55 | Mengelak daripada masalah saya. | Avoided my problem. |

| 56 | Mengundurkan diri dan cuba melihat keadaan yang sebenarnya. | Stepped back and tried to see things as they really are. |

| 57 | Membandingkan diri saya dengan orang lain yang kurang bernasib baik. | Compared myself to others who are less fortunate. |

| 58 | Meningkatkan bilangan perkara yang menyenangkan dalam hidup saya supaya saya mempunyai pandangan yang lebih positif. | Increased the number of pleasant things in my life so that I had a more positive outlook. |

| 59 | Cuba untuk tidak meninggalkan keadaan dan tidak mengakhirinya dengan teruk. | Tried not to burn my bridges behind me, but leave things open somewhat. |

| - | Overall Cronbach’s α | 95% CI (Lower -Upper) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skills Use Scale | 0.910 | (0.895 - 0.923) | ||

| - | If item dropped | - | ||

| Item | Cronbach's α | Item-rest Correlation | Mean | SD |

| 1. Bargained or compromised to get something positive from the situation | 0.908 | 0.427 | 2.134 | 0.937 |

| 2. Counted my blessings. | 0.907 | 0.474 | 2.618 | 0.654 |

| 4. Concentrated on something good that could come out of the whole thing. | 0.906 | 0.613 | 2.268 | 0.755 |

| 6. Made sure I'm responding in a way that doesn’t alienate others. | 0.908 | 0.424 | 2.186 | 0.888 |

| 9. Tried to get centered before taking any action. | 0.907 | 0.543 | 2.438 | 0.681 |

| 10. Talked to someone about how I’ve been feeling. | 0.907 | 0.459 | 1.706 | 0.944 |

| 11. Stood my ground and fought for what I wanted. | 0.907 | 0.538 | 2.314 | 0.764 |

| 13. Treated myself to something really tasty. | 0.909 | 0.355 | 2.147 | 0.899 |

| 16. Came up with a couple of different solutions to my problem. | 0.907 | 0.508 | 2.258 | 0.757 |

| 18. Accepted my strong feelings, but not let them interfere with other things too much. | 0.907 | 0.489 | 2.154 | 0.780 |

| 19. Focused on the good things in my life. | 0.906 | 0.626 | 2.395 | 0.709 |

| 21. Found something beautiful to look at to make me feel better. | 0.907 | 0.518 | 2.304 | 0.807 |

| 22. Changed something about myself so that I could deal with the situation better. | 0.906 | 0.549 | 2.255 | 0.802 |

| 23. Focused on the good aspects of my life and gave less attention to negative thoughts or feelings. | 0.906 | 0.590 | 2.167 | 0.827 |

| 26. Tried to distract myself by getting active. | 0.907 | 0.518 | 2.013 | 0.887 |

| 27. Been aware of what has to be done, so I've been doubling my efforts and trying harder to make things work. | 0.905 | 0.620 | 2.225 | 0.788 |

| 29. Soothed myself by surrounding myself with a nice fragrance of some kind. | 0.910 | 0.339 | 1.124 | 1.091 |

| 31. Listened to or played music that I found relaxing. | 0.909 | 0.342 | 2.343 | 0.832 |

| 33. Accepted the next best thing to what I wanted. | 0.908 | 0.386 | 2.013 | 0.777 |

| 34. Told myself things could be worse. | 0.913 | 0.072* | 1.797 | 0.991 |

| 35. Occupied my mind with something else. | 0.910 | 0.288 | 2.072 | 0.899 |

| 36. Talked to someone who could do something concrete about the problem. | 0.907 | 0.487 | 1.703 | 0.930 |

| 38. Tried not to act too hastily or follow my own hunch. | 0.908 | 0.440 | 1.918 | 0.874 |

| 39. Changed something so things would turn out right. | 0.906 | 0.603 | 2.144 | 0.776 |

| 40. Pampered myself with something that felt good to the touch (e.g., a bubble bath or a hug). | 0.910 | 0.348 | 1.376 | 1.151 |

| 42. Thought how much better off I was than others. | 0.911 | 0.182* | 0.928 | 0.858 |

| 43. Just took things one step at a time. | 0.911 | 0.183* | 1.693 | 0.907 |

| 44. Did something to feel a totally different emotion (like go to a funny movie). | 0.909 | 0.332 | 2.056 | 0.923 |

| 47. Focused my energy on helping others. | 0.907 | 0.473 | 2.147 | 0.794 |

| 49. Made sure to take care of my body and stay healthy so that I was less emotionally sensitive. | 0.906 | 0.542 | 2.190 | 0.836 |

| 50. Told myself how much I had already accomplished. | 0.906 | 0.555 | 1.954 | 0.947 |

| 51. Made sure I respond in a way so that I could still respect myself afterwards. | 0.907 | 0.498 | 2.255 | 0.826 |

| 53. Made a plan of action and followed it. | 0.906 | 0.544 | 2.124 | 0.796 |

| 54. Talked to someone to find out about the situation. | 0.907 | 0.457 | 2.157 | 0.884 |

| 56. Stepped back and tried to see things as they really are. | 0.909 | 0.333 | 1.984 | 0.847 |

| 57. Compared myself to others who are less fortunate. | 0.911 | 0.242 | 1.510 | 1.053 |

| 58. Increased the number of pleasant things in my life so that I had a more positive outlook. | 0.905 | 0.641 | 2.225 | 0.817 |

| 59. Tried not to burn my bridges behind me, but leave things open somewhat. | 0.906 | 0.550 | 2.173 | 0.821 |

| - | Overall Cronbach’s α | 95% CI (Lower -Upper) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Dysfunctional Coping Factor | 0.836 | (0.808 - 0.861) | ||

| Item | Cronbach's α | Item-rest Correlation | Mean | SD |

| 3. Blamed myself. | 0.819 | 0.583 | 1.523 | 0.888 |

| 5. Kept feelings to myself. | 0.827 | 0.454 | 2.186 | 0.838 |

| 8. Hoped a miracle would happen. | 0.830 | 0.406 | 2.075 | 0.943 |

| 12. Refused to believe that it had happened. | 0.828 | 0.441 | 1.193 | 0.901 |

| 14. Criticized or lectured myself. | 0.820 | 0.559 | 1.748 | 0.991 |

| 17. Wished I were a stronger person — more optimistic and forceful. | 0.838 | 0.223* | 2.507 | 0.674 |

| 20. Wished that I could change the way that I felt. | 0.826 | 0.471 | 2.271 | 0.819 |

| 25. Felt bad that I couldn't avoid the problem. | 0.818 | 0.598 | 1.784 | 0.930 |

| 32. Gone on as if nothing had happened. | 0.830 | 0.397 | 1.944 | 0.883 |

| 37. Tried to make myself feel better by eating, drinking, smoking, taking medication, etc. | 0.844 | 0.208* | 0.950 | 1.059 |

| 41. Avoided people. | 0.825 | 0.475 | 1.415 | 1.050 |

| 45. Wished the situation would go away or somehow be finished. | 0.814 | 0.646 | 2.049 | 0.976 |

| 46. Kept others from knowing how bad things were. | 0.823 | 0.527 | 1.990 | 0.921 |

| 52. Wished that I could change what had happened. | 0.823 | 0.513 | 2.114 | 0.943 |

| 55. Avoided my problem. | 0.829 | 0.408 | 1.327 | 0.960 |

| - | Overall Cronbach’s α | 95% CI (Lower -Upper) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blaming Others Factor | 0.723 | (0.673 - 0.768) | ||

| - | If Item Dropped | - | ||

| Item | Cronbach's α | Item-rest Correlation | Mean | SD |

| 7. Figured out who to blame. | 0.650 | 0.565 | 1.046 | 0.926 |

| 15. Took it out on others. | 0.662 | 0.546 | 0.778 | 0.787 |

| 24. Got mad at the people or things that caused the problem. | 0.670 | 0.508 | 1.297 | 0.872 |

| 28. Thought that others were unfair to me. | 0.680 | 0.477 | 1.245 | 0.976 |

| 30. Blamed others. | 0.624 | 0.685 | 0.814 | 0.773 |

| 48. Found out what the other person was responsible. | 0.795 | 0.060* | 1.931 | 0.894 |

| - | 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Indicator | Estimate | Std. Error | z-value | p | Lower | Upper |

| Skills use | 1. Bargained or compromised to get something positive from the situation | 0.382 | 0.053 | 7.223 | < .001 | 0.278 | 0.485 |

| 2. Counted my blessings. | 0.373 | 0.035 | 10.611 | < .001 | 0.304 | 0.442 | |

| 4. Concentrated on something good that could come out of the whole thing. | 0.521 | 0.039 | 13.475 | < .001 | 0.445 | 0.596 | |

| 6. Made sure I'm responding in a way that doesn’t alienate others. | 0.377 | 0.050 | 7.556 | < .001 | 0.279 | 0.475 | |

| 9. Tried to get centered before taking any action. | 0.419 | 0.036 | 11.649 | < .001 | 0.348 | 0.489 | |

| 10. Talked to someone about how I’ve been feeling. | 0.427 | 0.053 | 8.114 | < .001 | 0.324 | 0.530 | |

| 11. Stood my ground and fought for what I wanted. | 0.462 | 0.040 | 11.407 | < .001 | 0.383 | 0.541 | |

| 13. Treated myself to something really tasty. | 0.305 | 0.051 | 5.925 | < .001 | 0.204 | 0.406 | |

| 16. Came up with a couple of different solutions to my problem. | 0.406 | 0.041 | 9.857 | < .001 | 0.325 | 0.487 | |

| 18. Accepted my strong feelings, but not let them interfere with other things too much. | 0.406 | 0.043 | 9.522 | < .001 | 0.323 | 0.490 | |

| 19. Focused on the good things in my life. | 0.520 | 0.035 | 14.648 | < .001 | 0.450 | 0.589 | |

| 21. Found something beautiful to look at to make me feel better. | 0.437 | 0.044 | 9.968 | < .001 | 0.351 | 0.523 | |

| 22. Changed something about myself so that I could deal with the situation better. | 0.467 | 0.043 | 10.897 | < .001 | 0.383 | 0.551 | |

| Skills use | 23. Focused on the good aspects of my life and gave less attention to negative thoughts or feelings. | 0.562 | 0.042 | 13.231 | < .001 | 0.479 | 0.645 |

| 26. Tried to distract myself by getting active. | 0.479 | 0.048 | 9.957 | < .001 | 0.385 | 0.574 | |

| 27. Been aware of what has to be done, so I've been doubling my efforts and trying harder to make things work. | 0.548 | 0.040 | 13.658 | < .001 | 0.470 | 0.627 | |

| 29. Soothed myself by surrounding myself with a nice fragrance of some kind. | 0.354 | 0.063 | 5.652 | < .001 | 0.231 | 0.477 | |

| 31. Listened to or played music that I found relaxing. | 0.252 | 0.048 | 5.245 | < .001 | 0.158 | 0.346 | |

| 33. Accepted the next best thing to what I wanted. | 0.264 | 0.044 | 5.947 | < .001 | 0.177 | 0.351 | |

| 34. Told myself things could be worse. | -0.024* | 0.059 | -0.413 | 0.680 | -0.139 | 0.091 | |

| 35. Occupied my mind with something else. | 0.193 | 0.052 | 3.668 | < .001 | 0.090 | 0.295 | |

| 36. Talked to someone who could do something concrete about the problem. | 0.427 | 0.052 | 8.226 | < .001 | 0.325 | 0.528 | |

| 38. Tried not to act too hastily or follow my own hunch. | 0.402 | 0.049 | 8.254 | < .001 | 0.306 | 0.497 | |

| 39. Changed something so things would turn out right. | 0.489 | 0.041 | 12.012 | < .001 | 0.409 | 0.569 | |

| 40. Pampered myself with something that felt good to the touch (e.g., a bubble bath or a hug). | 0.332 | 0.066 | 4.999 | < .001 | 0.202 | 0.463 | |

| 42. Thought how much better off I was than others. | 0.123 | 0.050 | 2.442 | 0.015 | 0.024 | 0.222 | |

| 43. Just took things one step at a time. | 0.109 | 0.053 | 2.039 | 0.041 | 0.004 | 0.213 | |

| 44. Did something to feel a totally different emotion (like go to a funny movie). | 0.239 | 0.054 | 4.463 | < .001 | 0.134 | 0.344 | |

| 47. Focused my energy on helping others. | 0.397 | 0.044 | 9.079 | < .001 | 0.311 | 0.482 | |

| 49. Made sure to take care of my body and stay healthy so that I was less emotionally sensitive. | 0.521 | 0.044 | 11.848 | < .001 | 0.435 | 0.608 | |

| 50. Told myself how much I had already accomplished. | 0.583 | 0.050 | 11.665 | < .001 | 0.485 | 0.681 | |

| 51. Made sure I respond in a way so that I could still respect myself afterwards. | 0.452 | 0.045 | 10.097 | < .001 | 0.364 | 0.540 | |

| 53. Made a plan of action and followed it. | 0.471 | 0.042 | 11.101 | < .001 | 0.388 | 0.554 | |

| 54. Talked to someone to find out about the situation. | 0.395 | 0.049 | 7.984 | < .001 | 0.298 | 0.492 | |

| 56. Stepped back and tried to see things as they really are. | 0.280 | 0.049 | 5.758 | < .001 | 0.184 | 0.375 | |

| General dysfunctional coping | 3. Blamed myself. | 0.581 | 0.049 | 11.955 | < .001 | 0.486 | 0.676 |

| 5. Kept feelings to myself. | 0.423 | 0.048 | 8.790 | < .001 | 0.328 | 0.517 | |

| 8. Hoped a miracle would happen. | 0.416 | 0.055 | 7.564 | < .001 | 0.308 | 0.523 | |

| 12. Refused to believe that it had happened. | 0.436 | 0.052 | 8.399 | < .001 | 0.334 | 0.538 | |

| 14. Criticized or lectured myself. | 0.635 | 0.054 | 11.682 | < .001 | 0.528 | 0.741 | |

| 17. Wished I were a stronger person — more optimistic and forceful. | 0.171 | 0.041 | 4.199 | < .001 | 0.091 | 0.251 | |

| 20. Wished that I could change the way that I felt. | 0.423 | 0.047 | 9.030 | < .001 | 0.331 | 0.515 | |

| 25. Felt bad that I couldn't avoid the problem. | 0.638 | 0.050 | 12.823 | < .001 | 0.540 | 0.735 | |

| 32. Gone on as if nothing had happened. | 0.361 | 0.052 | 6.937 | < .001 | 0.259 | 0.463 | |

| 37. Tried to make myself feel better by eating, drinking, smoking, taking medication, etc. | 0.223 | 0.072 | 3.094 | 0.002 | 0.082 | 0.364 | |

| 41. Avoided people. | 0.540 | 0.060 | 8.996 | < .001 | 0.422 | 0.658 | |

| 45. Wished the situation would go away or somehow be finished. | 0.670 | 0.053 | 12.751 | < .001 | 0.567 | 0.773 | |

| 46. Kept others from knowing how bad things were. | 0.532 | 0.052 | 10.316 | < .001 | 0.431 | 0.633 | |

| 52. Wished that I could change what had happened. | 0.525 | 0.053 | 9.852 | < .001 | 0.421 | 0.629 | |

| 55. Avoided my problem. | 0.398 | 0.057 | 7.050 | < .001 | 0.288 | 0.509 | |

| Blaming others | 7. Figured out who to blame. | 0.623 | 0.051 | 12.210 | < .001 | 0.523 | 0.723 |

| 15. Took it out on others. | 0.525 | 0.044 | 12.039 | < .001 | 0.440 | 0.611 | |

| 24. Got mad at the people or things that caused the problem. | 0.524 | 0.050 | 10.525 | < .001 | 0.426 | 0.622 | |

| 28. Thought that others were unfair to me. | 0.560 | 0.056 | 10.046 | < .001 | 0.451 | 0.669 | |

| 30. Blamed others. | 0.641 | 0.040 | 15.895 | < .001 | 0.562 | 0.721 | |

| 48. Found out what the other person was responsible. | 0.069* | 0.056 | 1.240 | 0.215 | -0.040 | 0.179 | |